Neptune Problems vs. Vulcan Problems

This isn't about astrology, I promise.

In the 19th century, astronomers observed that Uranus's orbit didn't obey the laws of gravity. The elliptical path drifted further out than their calculations dictated it should, based on the known influences on the orbit.

There were two options: either gravity didn't work how people thought it did, or there was an as-of-yet unobserved influence tugging at Uranus. Gravity seemed to work everywhere else, so the second option was selected and the "Dark Planet" theory was born.

From 1841-1846, John Couch Adams worked on the the math in Cornwall and Cambridge, while Urbain Le Verrier did the same in France. The two worked independently, seemingly without knowledge of one another's work, but within three days of each other reported their solutions: Le Verrier's to the French Academy on August 31st, 1846 and Adams's to the Greenwich Observatory on September 2nd.

While both men ran the numbers, Le Verrier's calculations were passed onto Berlin, where the observations were made first. Neptune was found almost exactly where Le Verrier anticipated it would be, and Uranus's orbit was explained. Two astronomical mysteries solved by Le Verrier "with the point of his pen" (as François Arago said).

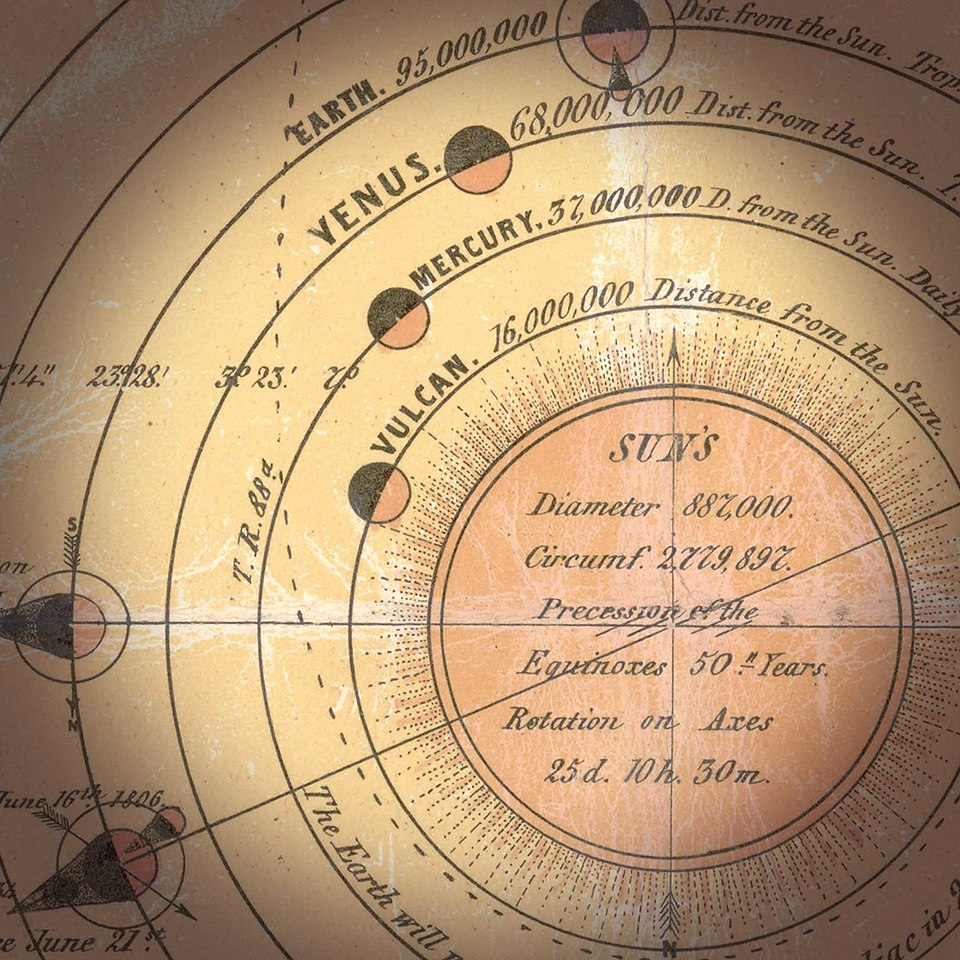

But Mercury's orbit had a similar problem: the known bodies and forces drew a path that didn't align with reality. Le Verrier was up for the challenge once more, looking at the data and declaring that there must be a missing body. He'd found the hidden influence on Uranus, and this problem looked to be the same. This theory, bolstered by reports of unknown objects passing in front of the Sun, led him to declare the planet Vulcan had been found on the far side of Mercury.

Live long and prosper! Adding a hypothetical Vulcan of the right dimensions to a map of the solar system fixed the math, and all was right in the world. Le Verrier becomes the first person to discover two planets in our solar system, and that's why we all know his name today.

Except, that wasn't the solution. The dots astronomers believed to be Vulcan were actually sun spots (accidentally discovered here for the first time), and the mystery of the cosmic toddler tugging on the hem of Mercury's orbit continued for another fifty years.

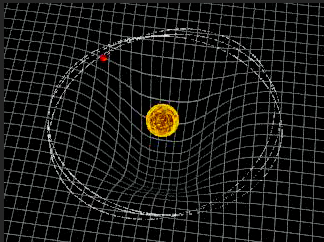

The real answer came with general relativity, when Einstein's theory explained that Mercury's distorted orbit reflected the curve in spacetime caused by the Sun's mass. It was one of the first demonstrations of the theory, bolder and easier to observe than the bending of light around gravity wells.

There was no missing planet, there was an entirely missing dimension to the problem.

These two stories sit beautifully together in the mind. Nearly identical problems, radically different solutions. This wonderful Kurzgesagt video takes this framework to explore some new issues facing cosmology, but the concept merits more exploration of its own.

Neptune Problems

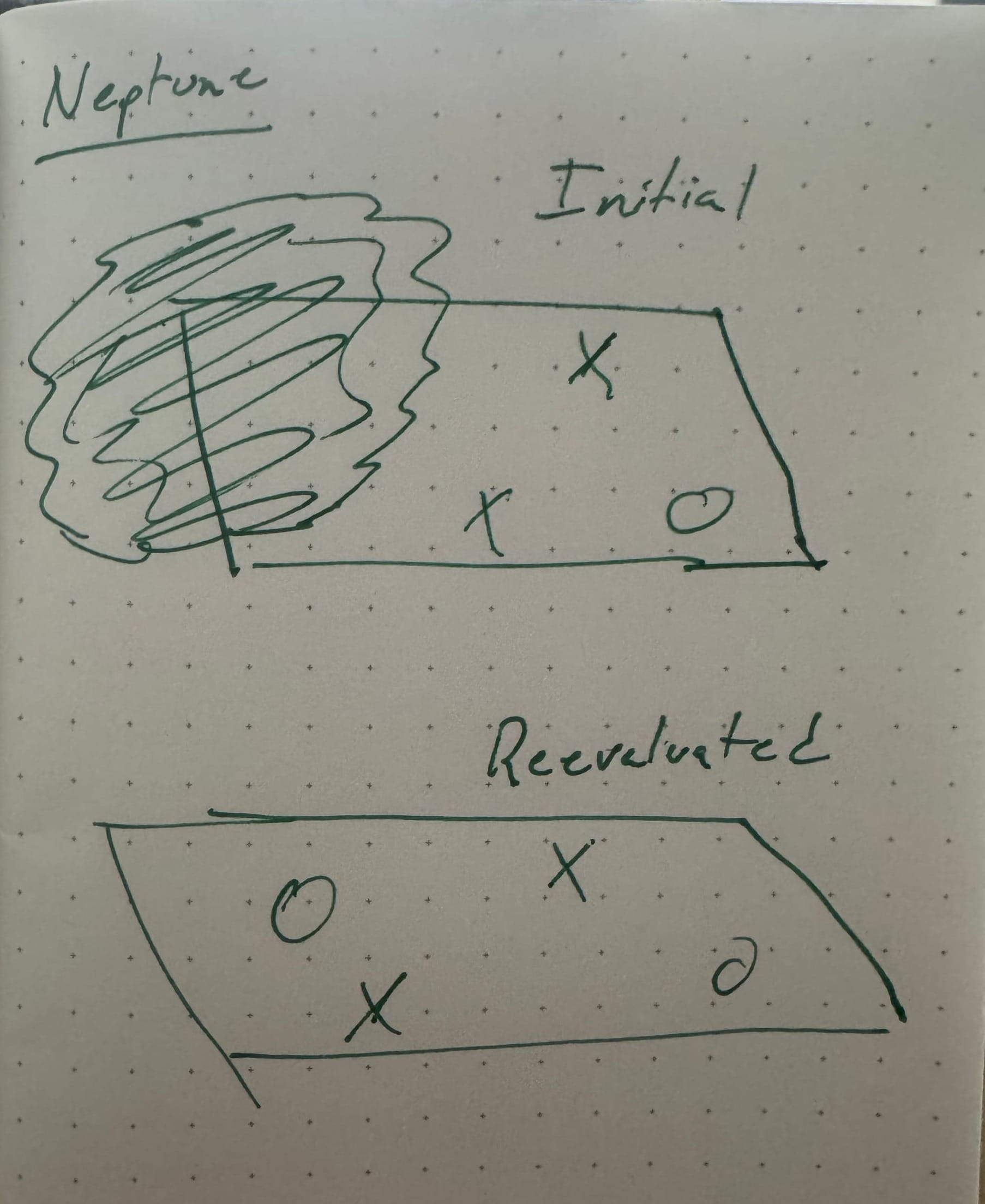

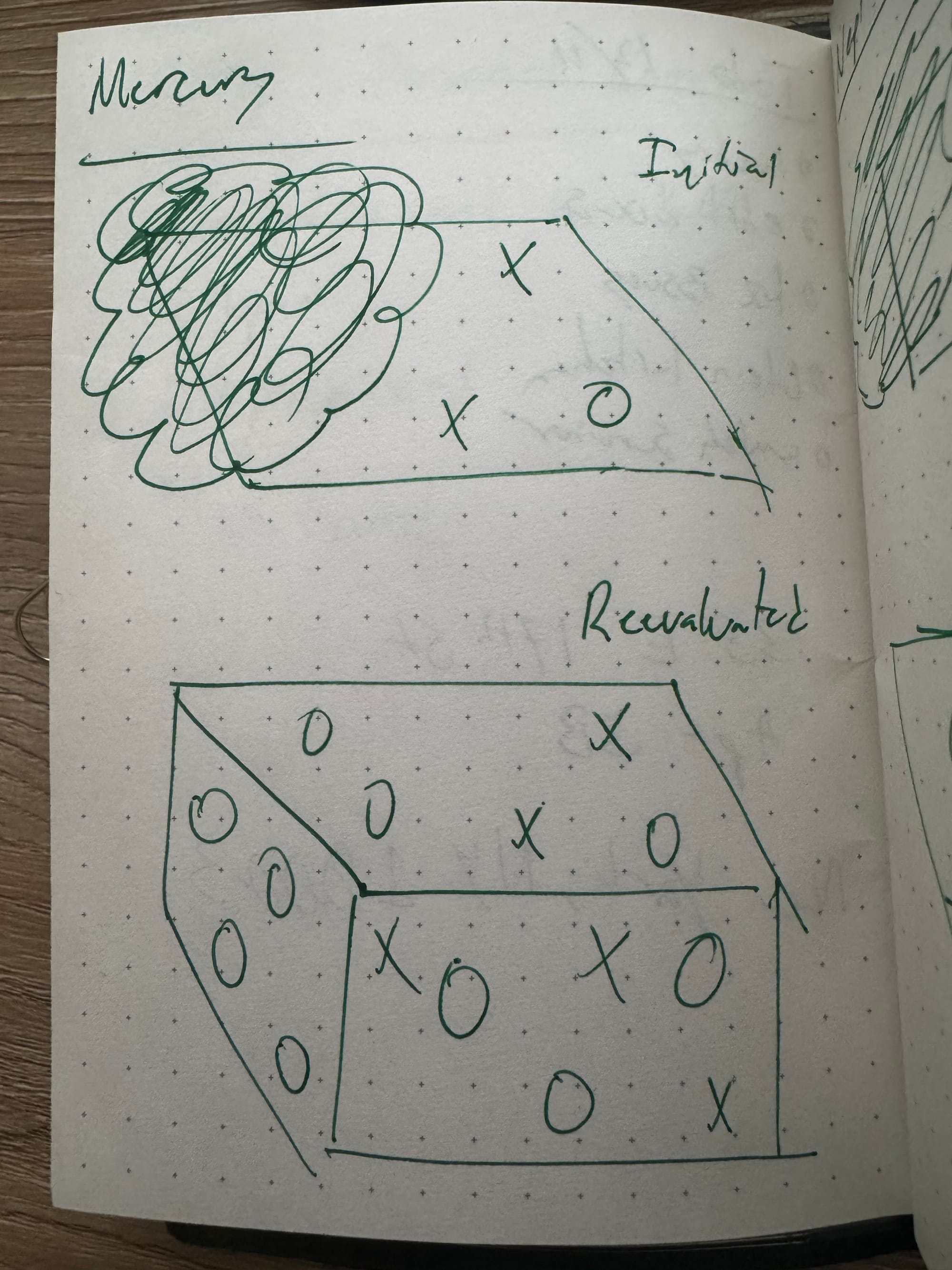

The dimensions of the perceived playing field are correct, but not all of the players are accounted for.

For example, an apartment building struggles to rent out units. Management tries lowering fees, adds free coffee to the lobby, but nothing works. They're stumped until they go outside and realize that the "Units Available" sign collapsed in a windstorm weeks ago. All it took to solve the problem was looking around a bit more.

To address a Neptune Problem, reevaluate the situation, taking in the environment as completely as possible. Map out the known factors and identify their interplay, looking for gaps to study further. Hopefully this turns up some missing element that could bring the equation into balance.

If it doesn't, then you could be dealing with...

Vulcan Problems

The field being considered is incomplete, and while players might be missing, there are whole realms of influence missing from consideration as well.

Cracking problems like this is much harder. It's not about finding missing variables in the experiment, but about reconsidering the most fundamental premises and assumptions of the problem in the first place.

It took Einstein to figure out why Mercury moves the way it does. Sticking with Newtonian physics meant that other scientists were incapable of considering possibilities beyond their realms of expertise, but taking that step out of an operating mode is nearly impossible. It's part of why mathematicians and physicists tend to peak in the first two decades of their careers, completing their greatest work before their instincts calcify and their perspectives (almost always) stagnate. When you know something to be true, considering that it might be false, even for an experiment, can be a colossal challenge.

What does this mean for B2B sales?

Nothing. And everything.

What does that mean?

Preconceived notions are an inevitability. Our minds process the world through the unique and ultracomplex filters of our lived experiences, defining our individualized versions of reality before conscious thought even begins. When we are not used to living fully in the moment, doing so becomes nearly impossible.

Take this tribute for Shunryu Suzuki, the great Zen roshi whose talks became the classic Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind.

"A roshi is a person who has actualized that perfect freedom which is the potentiality for all human beings. He exists freely in the fullness of his whole being. The flow of his consciousness is not the fixed repetitive patterns of our usual self-centered consciousness, but rather arises spontaneously and naturally from the actual circumstances of the present. The results of this in terms of the quality of his life are extraordinary – buoyancy, vigor, straightforwardness, simplicity, humility, serenity, joyousness, uncanny perspicacity and unfathomable compassion. His whole being testifies to what it means to live in the reality of the present" (Trudy Dixon, editor of Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind, emphasis mine).

Cultivating the practice of presence is a wonderful thing. Developing a beginner's mind, an openness to the universe as it spills out before you rather than the version molded by internal judgements, it's a prerequisite for a fresh perspective. There's no guarantee that you'll be able to solve every Vulcan problem you face, but by embracing a willingness to say "I don't know what I don't know", you create more opportunity to reinterpret the field at hand.

We can't all be Zen masters, but we can all work on approaching the world with more open minds.